We had our neighbours over this week. They come from a very different cultural world to ours — they are Zulu.

I don’t even know where to begin speaking about cultures other than my own. As a white South African with Christian roots, their way of life couldn’t be more different from how I was raised — even though my own upbringing was more secular than anything else. I grew up in an insular home. High walls separated us from our neighbours, and we remained largely disconnected from the people around us in any meaningful way.

My neighbour Judi (a pseudonym) is one of eleven siblings. She was raised in community. As with anything, there are highs and lows. In her world, everyone knows everyone. Privacy is scarce. Your business is rarely only your own.

And yet, I’ve always longed for something like that — a felt sense of belonging to a larger whole. Of having many brothers and sisters, both inside and outside of family.

What I’ve come to learn about myself is that building cross-cultural bridges is something I love. And at the same time, it reliably takes me far outside my comfort zone. I know I’m going somewhere unfamiliar, and it’s not something I rush toward.

I think this is a built-in feature of purpose: it’s rarely something you hurry into, and there’s no obvious payoff for the ego. Something deeper inside says move. Go there. And it’s hard to explain why you would — except that not going somehow starts to feel more painful.

In that sense, purpose may be motivated more by pain than by calling.

At a certain point, it becomes harder to stay comfortable. Comfort itself turns into its own kind of enemy, because somewhere inside we’re longing for something beyond it.

Oliver Burkeman puts it this way:

“Resisting a task is usually a sign that it’s meaningful — which is why it’s awakening your fears and stimulating procrastination. You could adopt ‘Do whatever you’re resisting the most’ as a philosophy of life.”

Life Is Expensive

Halfway through the evening, Judi said something that stayed with me.

“You know,” she said, “it doesn’t matter if you have anything or not. If you have food or not. You carry this expensive gift called life.”

The word expensive stayed with me. Not precious. Not sacred. Expensive.

It broke the usual chain of haves and have-nots. It cut across circumstance. No matter where we come from, we all carry this “expensive” gift — life — and somehow we can never lose it.

Let’s name another feature of purpose here: a sense of rightness that arrives without effort, often without choice. Energy moves. Something aligns. And strangely, it feels less like you chose it and more like it chose you.

And often, what’s choosing you isn’t that sexy.

Disappearing

Back in modern life, purpose has become one of the most seductive words of our time. Everyone seems to be searching for it.

It’s slippery — sometimes present, sometimes gone. I might be sitting in front of a sunset, and suddenly there is no purpose at all. Just light. Just colour. Just being here.

In those moments, purpose doesn’t feel deliberate. It finds me rather than the other way around. And when it does, it undoes me. There’s no story left. No striving. Just presence.

Of course, we can’t rely on sunsets to guide our lives. But they reveal something important — not what purpose is, but what it feels like when we touch it.

This brings me to another feature of purpose, following Judi’s teaching: you disappear.

When purpose is real, your will doesn’t obstruct something larger. You become more like an empty chair. And emptiness is not easy.

Feeling full often feels safer. We lean into what we think we know. Into opinions, frustrations, fears, desires. Into other people’s certainty. Into borrowed directions.

But to encounter purpose, we often have to become emptier than we want to be. Which takes us right back to the beginning: emptiness touches the very thing we most resist. And, as Burkeman suggests, resistance is often the marker of where we need to go.

I’ve seen this same quality in music.

There’s a moment when a musician is fully absorbed — when effort disappears. It’s no longer clear whether the person is playing the instrument or the music is playing them.

Nothing feels performative. There’s no story about destiny or importance. Just skill, presence, surrender.

Nothing left but the music.

That feels like the difference between meaning that inflates purpose and meaning that right-sizes it. It’s not big or small — it just is, without story attached. And yet it moves us, quietly shaping a life that feels wider, thicker, more inclusive.

The Traps

There is a reward for following the harder impulses. They fill us in ways short-term fixes can’t. But even here, the experience is strange. It doesn’t feel like pleasure in the usual sense.

And still — who’s to say that going to a movie or sharing a meal with a friend isn’t part of purpose too? Sometimes those are precisely the things we don’t feel like doing — and we lose ourselves in them anyway.

With that groundwork, I want to name some of the traps.

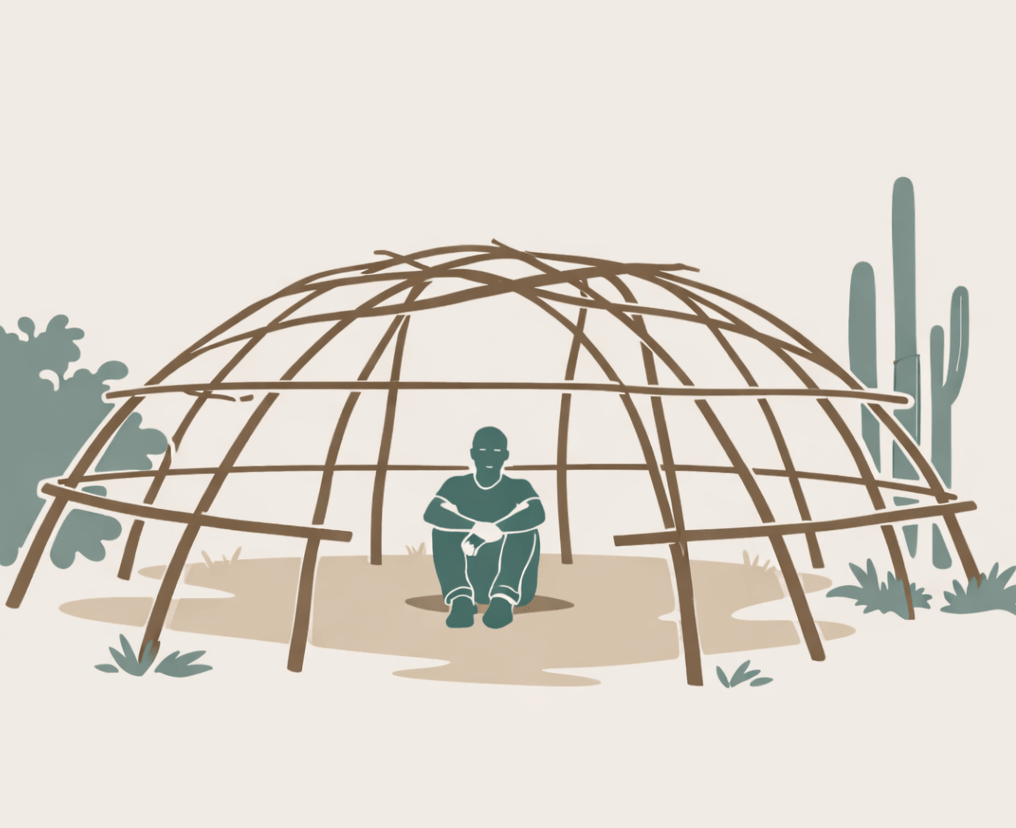

We often speak of purpose as if it were a destination — something to discover, claim, and finally inhabit. In spiritual communities especially, purpose gets dressed in colour and ceremony. The shaman on the pedestal. Feathers. Symbols. Mythic language.

If only I could live like that, we tell ourselves, then my life would finally make sense.

Purpose becomes something close enough to feel, distant enough to chase. And that chase can become its own form of suffering.

What’s rarely questioned is whether the way we relate to purpose actually pulls us away from the very thing we’re longing for.

A Project of Ego

We live in a meaning-hungry time. You can feel it in the air. Beneath productivity and self-improvement, there’s a longing — and I think it’s a valid one. Who wants to get lost in a world of superficiality?

Mythologists like Michael Meade speak about soul-level calling — archetypal energies we arrive carrying. The idea that life has a story etched into the soul, something waiting to be lived. I resonate with that. I don’t want to live as if all this is pointless. Even if we never know for sure, treating life as meaningful feels more useful to me.

And yet, this language can also seduce us. It can start to suggest that only a certain kind of life counts. A magical one. A meaningful one. A life with a clear arc.

So I find myself wondering about the ordinary.

The repetitive.

The dry and unremarkable.

Could that be purpose too?

More and more, I notice how easily purpose becomes something the ego puts on. A story of specialness. A promise that the suffering will make sense later. That the discomfort is leading somewhere elevated.

The ego isn’t the enemy. It’s protective. It wants things to cohere. Purpose gives it that — beautifully.

And that’s where the trap sits.

I’ve watched people step into “purposes” that weren’t really theirs. From the outside, you can feel it. They’re doing the thing because they think it will give them status, or legitimacy, or relief. Because it promises power, respect, belonging, or a way to fill the emptiness inside.

When purpose becomes identity — role, destiny — it gives the ego something to stand on.

True purpose, as I’m coming to understand it, is actually anti-ego. It keeps leading us to the one place the ego would rather not go. And strangely, that means we don’t have to search so hard.

What’s Left

So after all this, what’s left?

I want to offer a simple working definition:

purpose is making something with the conditions of your life exactly as you find them.

Your purpose is to make something out of the material that’s here.

Or, as Suleika Jaouad puts it, to be creative with your survival.

It’s alchemy. Looking at your life like a garden and thinking the way a gardener would: What can grow here? What needs tending? What needs time?

Your purpose is to tend that garden as a gardener would — seeing what needs doing, dreaming about the kind of garden you want to create. And a good garden needs compost. You could say all our pain and difficulty can be that compost.

Your purpose is to trust yourself to notice the movements — and to follow them. Simple like that.